The Flying Scud Trophy:

A Legacy of Racing, Rivalry, and Redemption

Few sporting trophies can claim a history as dramatic and intertwined with personal triumph and downfall as The Flying Scud trophy. Commissioned in 1867 by Henry Chaplin and the Duke of Newcastle, this sterling silver masterpiece embodies not just a remarkable era of horse racing but also one of its most legendary rivalries. Designed by the esteemed sculptor Joseph Edgar Boehm and crafted by the renowned silversmiths Barnard Brothers, the trophy remains a testament to a tale of love, betrayal, and ultimate victory.

A Scene of High Drama

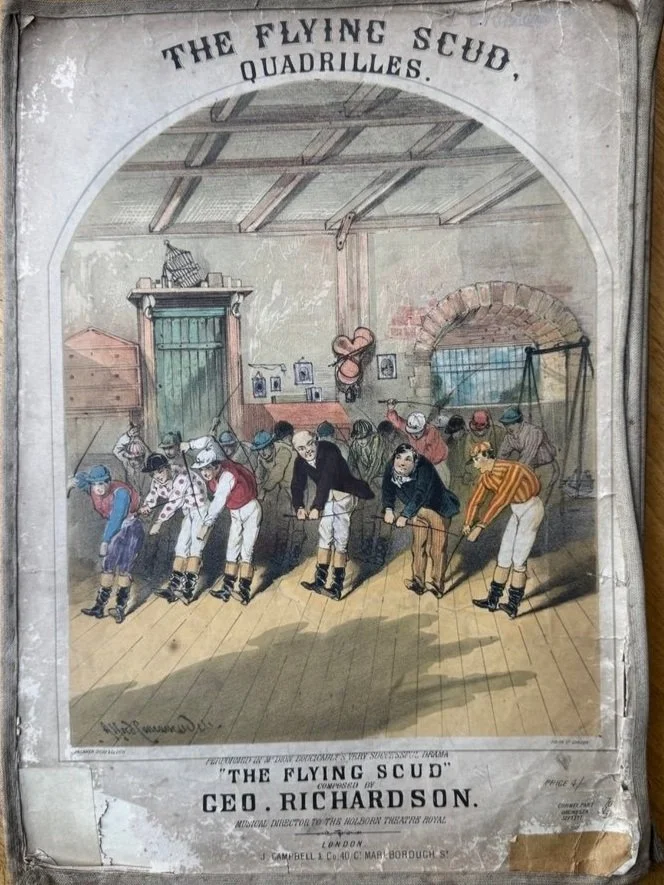

The inspiration for The Flying Scud trophy came from Dion Boucicault’s celebrated play of the same name, a racing drama that captivated audiences at the High Holborn Theatre. Chaplin, still riding the high of his triumph in the 1867 Derby with his horse Hermit, saw in the play a striking parallel to his own story. The chosen scene depicts the old jockey Nat Gosling discovering that his horse’s rider has been drugged on the eve of a race. In a desperate move, Gosling takes the reins himself, overcoming all odds to claim victory.

The manufacture of this celebrated racing prize was entrusted to Mr J.W. Benson of Old Bond Street. The design was selected by the stewards of Stamford racecourse, the Duke of Newcastle and Mr. Henry Chaplin.

The design selected is an interesting scene from Mr Dion Boucicault's sporting drama of "Flying Scud" At the close of the second act where the old jockey, Nat Gosling, who has not ridden a race for more than a quarter of a century, suddenly discovers that the rider of his favourite horse "Flying Scud," has been drugged on the eve of starting. He resolves to mount the animal himself and win the Derby.

Chaplin, who had defied all expectations to win the Derby with Hermit, chose this subject after he saw the play at the High Holborn Theatre.

Once completed, the trophy was presented at the Stamford Races on July 19, 1867. In an ironic twist, it was awarded to the very man it was meant to symbolically defeat —The Marquis of Hastings, whose horse Lecturer claimed victory in the Stamford Cup. But fate was not done with its cruel games. Just a year later, Hastings’ financial ruin led to the trophy passing into the hands of Henry Padwick, a moneylender who had claimed much of the Marquis’s estate as debt repayment. Records from the Chester Chronicle (November 28, 1868) confirm this transaction, marking the first of many changes in ownership.

An Heirloom Passed Through Generations

Padwick, a significant figure in racing circles, retained the trophy until his death in 1885, at which point it was inherited by his son, also named Henry Padwick. The trophy remained in the Padwick family until 1922, when it was purchased by J.W. Benson, the son of the original jeweller who had overseen its manufacture. This acquisition not only returned the trophy to its original commissioning family but also ensured its continued preservation.

In 1936, the trophy was bequeathed to a private family collection, where it has remained for nearly a century, a carefully guarded relic of a bygone era of horse racing. Now, in 2025, it has emerged once more, offered for private sale—a rare opportunity for collectors and historians alike to own a piece of equestrian history.

A Testament to Time and Triumph

The Flying Scud trophy is far more than an ornate silver centrepiece. It is a tangible link to one of horse racing’s most storied rivalries, a symbol of personal vindication, and an exquisite work of craftsmanship by some of the most renowned names in 19th-century silversmithing. Its journey—from the hands of Chaplin, through the fall of the Marquis of Hastings, to the collections of moneylenders and jewellers—has cemented its place as one of the most fascinating artefacts of its time.

As it now returns to the market, this extraordinary trophy carries with it the echoes of history—of a scandal that rocked high society, of a Derby that changed fortunes, and of a scene from the stage that became immortalised in silver. Its next owner will not just acquire an object of beauty but a piece of history, rich with drama, rivalry, and redemption.

The piece is in very good condition commensurate with its age and use as a family heirloom and table centrepiece. It comes complete with framed print of the scene by J. E. Boehm, the original musical score of The Flying Scud musical, various documents and 30+ pages of paperwork that have been amassed over decades of research detailing its extraordinary story.

For more information and to submit an offer, please get in touch via our contact us page.

The Flying Scud Musical by Dion Boucicault

This was the second play ever staged at the Tyne Theatre & Opera House, opening on 21st October 1867 for a two-week run. A play about doping a horse, it proved to be a great success throughout its run.

This was the second play ever staged at the Tyne Theatre & Opera House, opening on 21st October 1867 for a two-week run. A play about doping a horse, it proved to be a great success throughout its run.

Dion Boucicault first used the expression ‘‘I’ve got to see a man about a dog’ in his play "The Flying Scud or, A Four-Legged Fortune, written in London (Sept., 1866), a few months before before the dramatist emigrated to New York (source):

Quail [the lawyer]: I have just heard that the bill I discounted for you bearing Lord Woodbie's name, is a forgery. I give you twelve hours to find the money, and provide for it.

Mo [Davis, follower of the turf]: [Looking at watch] Excuse me, Mr. Quail, I can't stop; I've got to see a man about a dog. I forgot all about it till just now. [Act 4, Scene 1]

Contact Us

For more information, details or to make an offer; please use the contact us form.